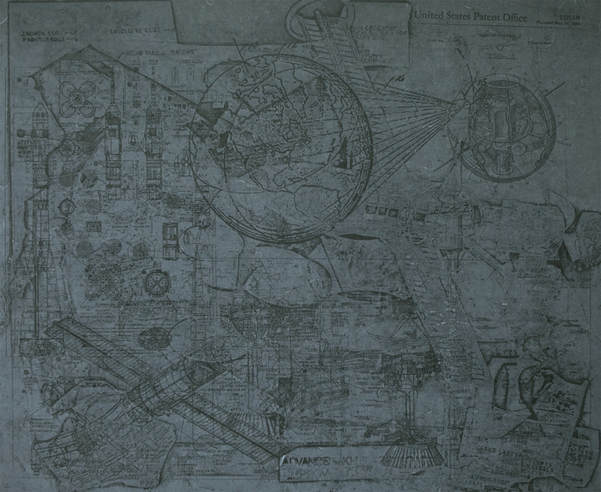

"E.V.A.C. (IV):TD/SAT:206x P.I./S.H.(W.O.S.)-A.S.R.S." 24" x 29"

Relief collagraph & digital laser engraved image, digital serigraphy, 2017

Relief collagraph & digital laser engraved image, digital serigraphy, 2017

Terry, Air Force, Iraq/Afghanistan

I was put on the Soviet Aviation Team, so that was all we did all day. I used to work the night shifts, and as the imagery would roll in at night that was all we would do, look at Soviet Air Fields and write reports all night long and let management know what the bad guys were up to.

At that point there were only three digital computer stations in the world that existed, and two were at the CIA and one was at SAC, Strategic Air Command. We had one station that was so large it had 200 hundred people, so you didn’t get to look at the computer for long. We had one copy that was the old style roll of satellite imagery and we had light tables. We’d lay them on there and you’d look with the optics and microscope. The film was on the satellite itself and they would take it and literally drop it off the satellite down to Earth. A parachute would come out and the team out in Hawaii would go and capture that film and bring it back and ship it off to D.C., process the imagery and make copies and send it all around the world so analysts could do their exploration.

I think one thing I learned was that it taught me to concentrate for a really long time; for example, if you’re looking at a high risk target and upper management is really concerned about this particular installation or what’s happening there, or something’s going down —you had to really focus —because you didn’t want to be the guy that missed something. It was very intense, very intense work, so again, when looking through those scopes you had to sweep the area and as you would go through, you would have to stop and focus on specific areas, and really look at equipment and focus on what was happening. Were they loading bombs onto this thing or was the plane under repair? You were trying to gather and figure out as much as you could, and what was happening at the point and time when the image was taken.

I was put on the Soviet Aviation Team, so that was all we did all day. I used to work the night shifts, and as the imagery would roll in at night that was all we would do, look at Soviet Air Fields and write reports all night long and let management know what the bad guys were up to.

At that point there were only three digital computer stations in the world that existed, and two were at the CIA and one was at SAC, Strategic Air Command. We had one station that was so large it had 200 hundred people, so you didn’t get to look at the computer for long. We had one copy that was the old style roll of satellite imagery and we had light tables. We’d lay them on there and you’d look with the optics and microscope. The film was on the satellite itself and they would take it and literally drop it off the satellite down to Earth. A parachute would come out and the team out in Hawaii would go and capture that film and bring it back and ship it off to D.C., process the imagery and make copies and send it all around the world so analysts could do their exploration.

I think one thing I learned was that it taught me to concentrate for a really long time; for example, if you’re looking at a high risk target and upper management is really concerned about this particular installation or what’s happening there, or something’s going down —you had to really focus —because you didn’t want to be the guy that missed something. It was very intense, very intense work, so again, when looking through those scopes you had to sweep the area and as you would go through, you would have to stop and focus on specific areas, and really look at equipment and focus on what was happening. Were they loading bombs onto this thing or was the plane under repair? You were trying to gather and figure out as much as you could, and what was happening at the point and time when the image was taken.